Nyurapayia Nampitjinpa, artist of a universe of song and desert law

Nicolas Rothwell TheAustralian 12:00AM February 1, 2013

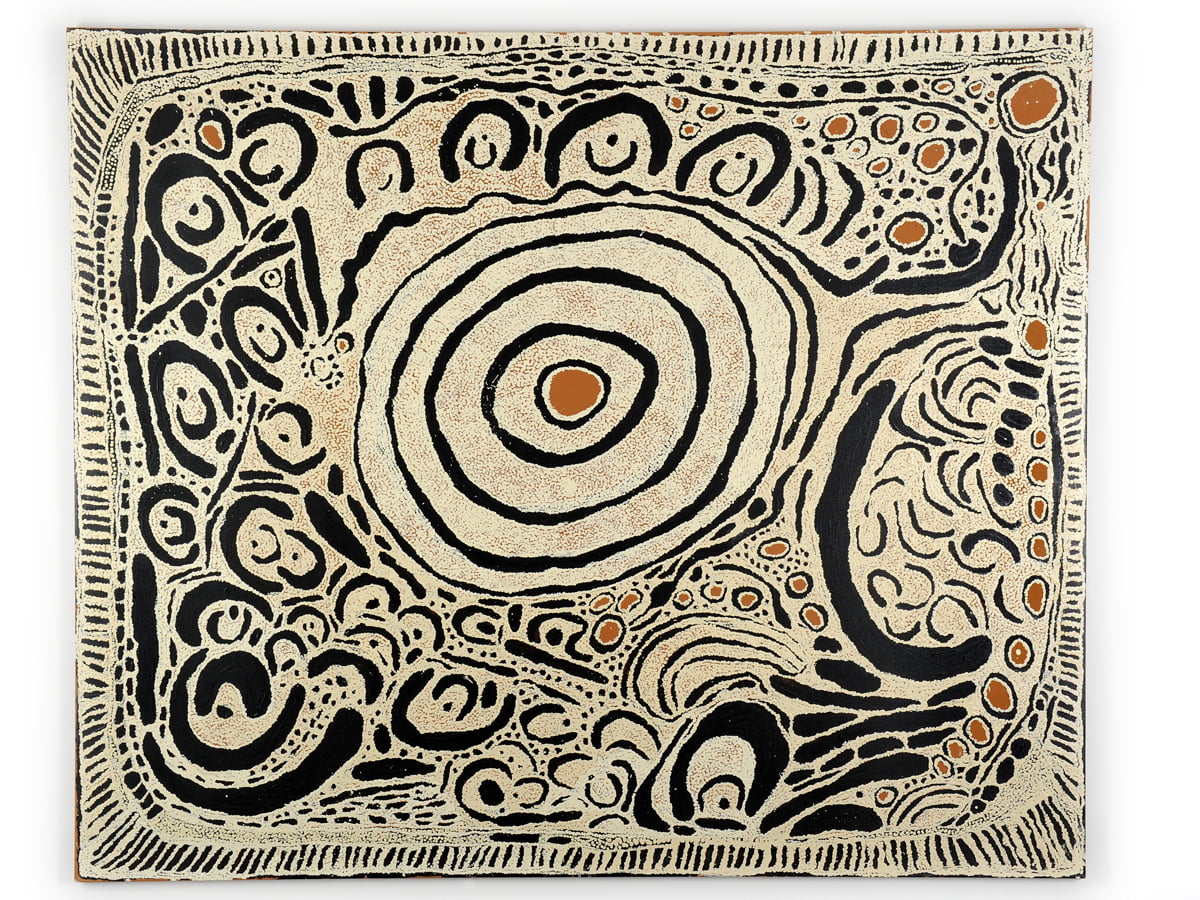

Nyurapayia Nampitjinpa, otherwise known as Mrs Bennett, helped shape the Aboriginal women’s painting movement. Picture: Steve Strike

IN the early hours of this Monday morning, in the far reaches of her ancestral country, Nyurapayia Nampitjinpa, the most forceful and overwhelming of the first western desert artists, reached the end of her remarkable life.

In any culture she would have stood out: she was a woman of will and pride, utterly confident, completely present in herself, yet generous, sentimental, awash with emotions keenly felt.

She could neither read nor write, yet she held in her head a universe of song and sacred knowledge. She was at the pinnacle of desert law: in her art, which was nothing but a translated image of that law and culture, she was a fierce expressionist. But it was her circumstances as much as her innate character that made her and shaped her unusual trajectory. No one will live a life like hers again.

She was born in Pitjantjatjara country, near the site of today’s Docker River community. She spent much of her childhood at Pangkupirri, a set of sheltered rockholes deep in the range-folds of the Gibson Desert. She was raised in an extended nomad familial group. She saw no white men until she was in her teens, although she had heard strange tales of their presence on the fringes of the vast sand-dune terrain she travelled through.

She remembered well her first, fleeting contact with the outside world. It came in a cool season: her father and his two brothers led their children on a cautious journey westwards, through the desert oak country, over dry creeks for days on end, until they reached the new mission compound at Warburton. From a safe distance they stared over the fence at the white people working there, then retreated to the bush again.

Those were years, for Nyurapayia, of learning the country, of immersion in ceremonial cycles, of deep study of the desert world and its creatures, both visible and invisible. She became a magic healer; she married the tranquil, solemn John John Bennett Tjapangati. By then western influence was spreading through the desert: engagement with that world was becoming inevitable.

The pair walked in together from the bush to Haasts Bluff settlement in the Ulumbara Ranges and began a new kind of life. There they encountered the mission strain of Christian belief, which had some resonances with the old religion of their hearts.

Even in those times, at rations depots and settlements, Nyurapayia was a figure of great and growing authority. She loved her culture, she performed it, she imprinted it within herself and became it: in this guise she was a key to the dispersed yet tight-linked society of the western desert. In recent years, whenever old women, themselves revered leaders, came face to face with Nyurapayia they would fall to their knees and hug her, and begin to sing the ancient songs she had taught them decades earlier in sacred dialects.

In the 1980s, together with Mr Bennett, Nyurapayia moved to Kintore, the new western settlement of the Pintupi, set closer to their traditional lands, and then on to Tjukurla, across the West Australian border. They lived there quietly and raised their daughter, Dorcas, and a son who died in early adulthood. Mr Bennett painted for Papunya Tula Artists, and gained a reputation for careful, introspective work.

Nyurapayia, though, was quite a different kind of artist. Front-foot, dynamic, authoritative, she helped shape the women’s painting movement that sprang up in the mid-1990s: she was close to the key painters; they influenced each other. Indeed their work was so intertwined it makes compelling sense to see this movement in its early stages as a collective enterprise. Then came sadness: Mr Bennett died, a decade ago. For all her magnificence, Mrs Bennett was alone.

Few, though, would have been able to predict the course her life then took. For the art centre staff at Papunya Tula, who had a dozen self-possessed old women to deal with, she was a handful: a queen who knew herself to be one, and expected to be treated as such. They were able to coax only mid-grade, formulaic works from her.

Her demanding catch-cry – “Mrs B, No 1”- originated at this time. Eventually she left Kintore and fell in with the roughest of the rough diamonds of the desert art trade, Chris Simon, who took her in and worked

her, and fell for her manner and her character: indeed he came to love and admire her, and he rebuilt his Yanda Art business around her.

These were the boom years of the Aboriginal art bazaar, Nyurapayia was in her early 70s, living comfortably, well cared for and hitting her creative peak. By day she would pour out large, complex canvases depicting her ancestral rockholes in dark, curved lines on white, shimmering grounds.

When rest-time came she would sit and watch films of “Inma”- old ceremonial dances from the Pitjantjatjara deserts – and sing to herself and laugh.

The upshot: a suite of paintings that now fill the great private Aboriginal art collections of the world and change hands for hundreds of thousands of dollars apiece. The twist: none is in Australian state or national galleries, which regard work from private dealers as beyond the pale.

Mrs Bennett, though, was happy with her fate in her last years: intensely happy, though the culture world she came from was in the past, and there were no longer nomad families in the far deserts, at the rockholes, singing.

She had fulfilled herself, and shown outsiders all the splendours of her realm. She held court, and painted: she lived for years in seemingly strong health with failing kidneys. When the time came, she demanded to be taken to the Wanarn aged home in the Ngaanyatjarra lands, to be in her country. Her time there was very short. She knew. The night before she died she sang old songs from her birth country; she spoke to her classificatory sister by telephone, and they prayed together. In the morning, she, and a whole world with her, was gone.

She is survived by her daughter, Dorcas Bennett; the funeral will be held in the western desert some weeks from now.

This large painting is still available -please inquire. vickie@silverplumegallery.com.au